Now I’m seeing evidence of cottages everywhere in my house.

And then there are the many miniatures – a sort of ‘cottage chic’.

It’s no wonder that my brother said, on Friday, that he hopes he dies before I do so he doesn’t have to clear out my house. That comment prompted me to weed my bookshelves in the weekend and give away two boxes of books. I expect he won’t notice the difference!

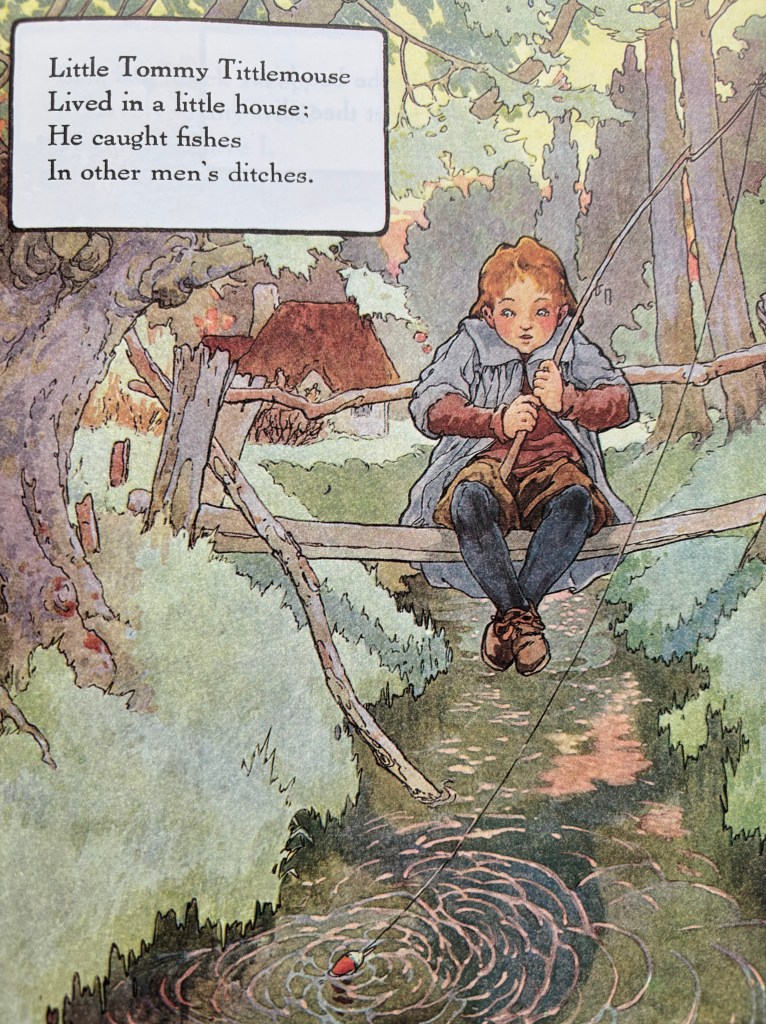

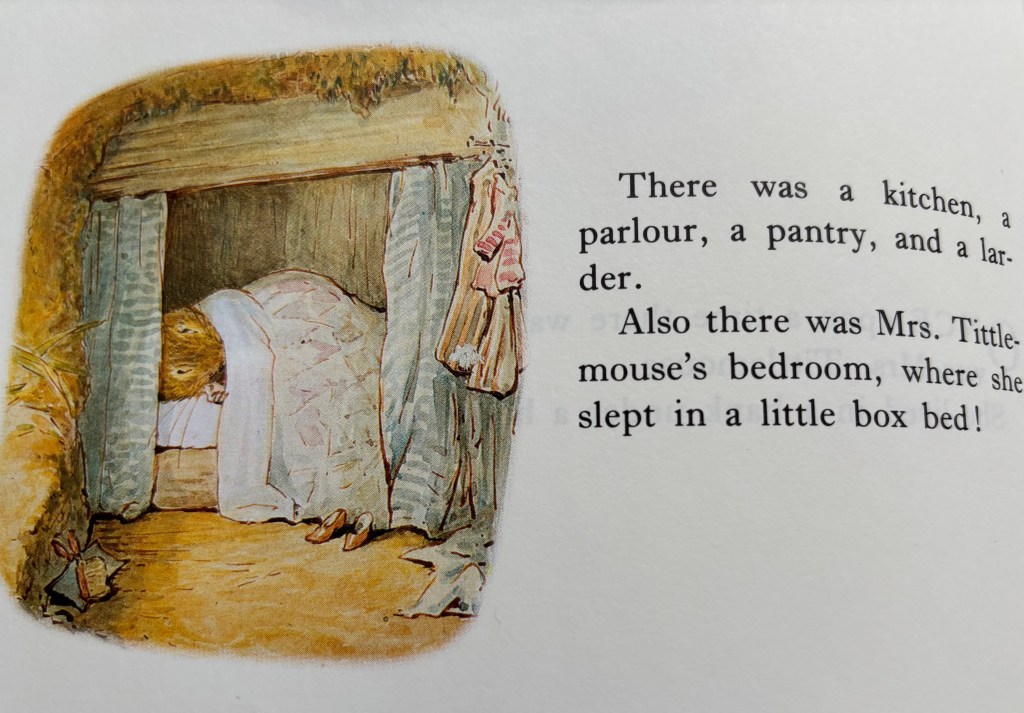

I suspect childhood reading was the source of my fascination with cottages. These pictures are from books I won’t be giving away.

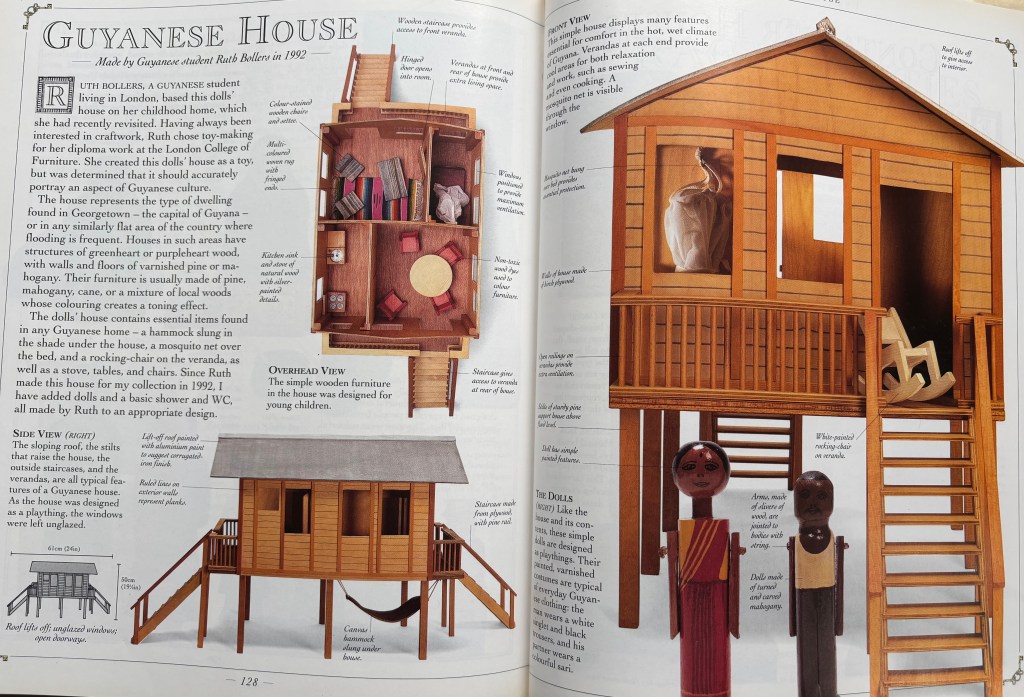

Books with cut-away interiors intrigue me, such as the last photo (above) of a neolithic French rural cottage. As Katherine Mansfield wrote in The Doll’s House: “Why don’t all houses open like that? How much more exciting than peering through the slit of a door into a mean little hall with a hat-stand and two umbrellas!”

My favourite childhood book was Miss Happiness and Miss Flower by Rumer Godden. In it, a Japanese dolls house is built, similar to the one in my copy of The Ultimate Dolls’ House Book by Faith Eaton, along with other interesting cottages, reminding me of the Folk Museum I visited in Korea which replicated the interiors of houses over time.

It’s not only children’s books which feature cottages. There are many books about women (or men, as in The Searcher by Tana French) who retreat to a country cottage to regroup and reshape their lives, with mixed success, such as in Falling by Elizabeth Jane Howard. Miss Marple lives in a cottage in the English village of St Mary Mead. Tove Jansson’s fictional family in The Summer Book live in a cottage on a Finnish island. Other authors have shown the disadvantages of the cottage: Jane Austen in Sense and Sensibility, Claire Fuller in Unsettled Ground. Still, somehow, the romance of the cottage lives on, whether it’s a place of retreat or a place to set out from on adventures.