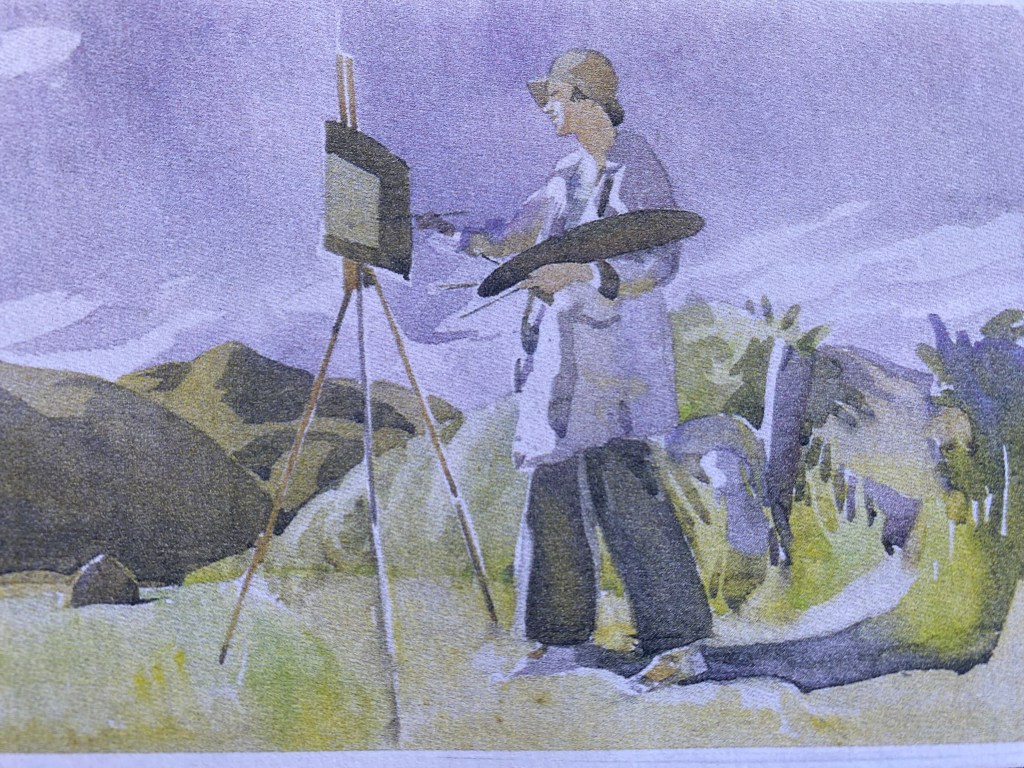

The artist featured in the exhibition Encountering Aotearoa at the Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū is Cora-Allan Lafaiki-Twiss (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Tumutumu, Nuie – Liku, Alofi). I am fascinated by her work. She went by boat around Aotearoa to look at the land and sea. In part, this was to see the land as the crew of the Endeavour might have seen it – with Tupaia and his assistant Taiata on board – as they circumnavigated and mapped the land. Cora-Allan asked her pāpā, Kelly Lafaiki (Nuie – Liku, Alofi) to accompany her as assistant on the journey. Videos screen on a wall, documenting the journey and the making of the work.

Frames around many of the paintings remind me of boat windows with their rounded edges and toughened glass. The artist uses hiapo, traditional mulberry bark paper often known as tapa cloth. It was soaked in sea water in each place a work was created. I looked at the back of the hanging paintings and could see where the sheets of paper had been joined and I could appreciate its texture and thickness.

The pigments used are from the whenua (land). So the making of the work is as fascinating as the paintings themselves. In a glass case, are some sketchbooks and a marvellous wooden toolkit which folds out, with a sliding drawer in the base and a leather handle. This would have been ideal when working from a boat.

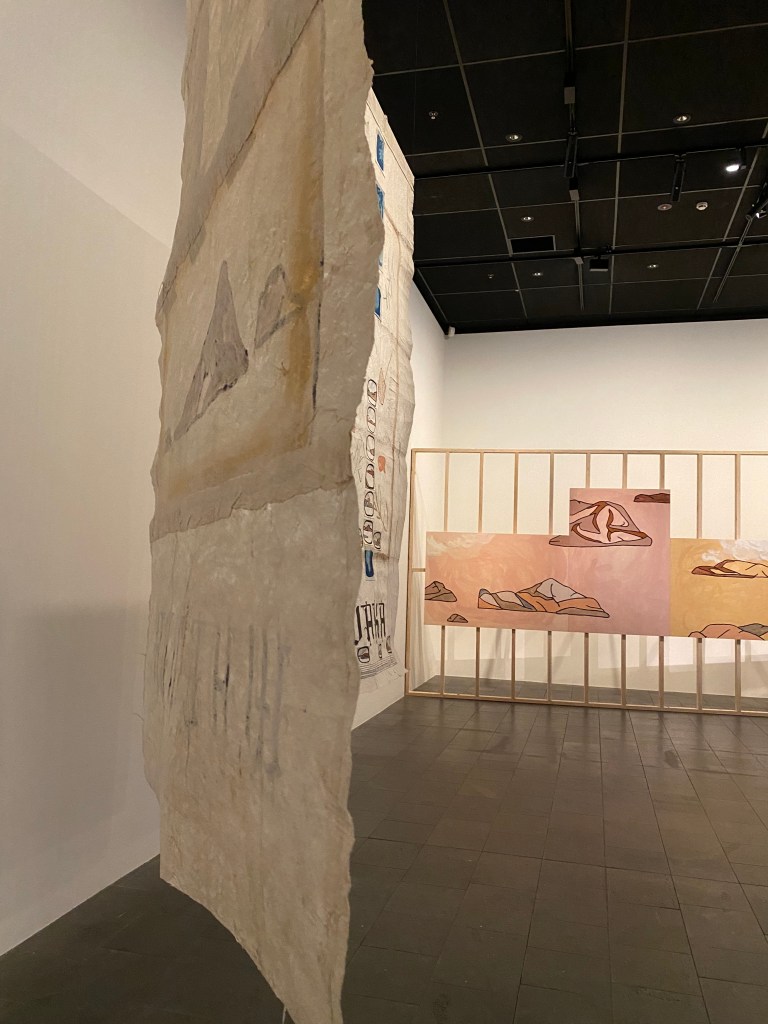

A panoramic sea view on panels stretches across the gallery space on a wooden frame.

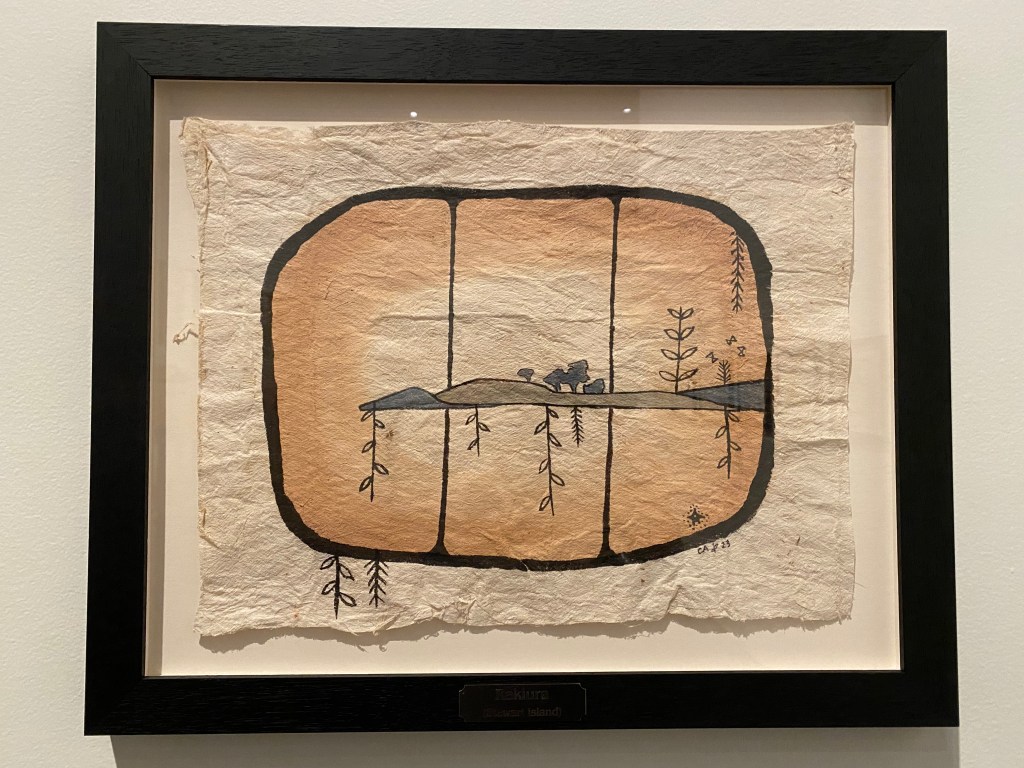

In the entrance to the exhibition, these islands seem to float on the grey/blue background.

Large hanging paintings lead you further in. The details are intricate and significant, with traditional and contemporary elements, and the photos don’t do them justice.

I look forward to visiting the exhibition again.

Post Script: I particularly liked the painting Rakiura. Later, I realised I was wearing a Glowing Sky jersey which seemed appropriate being a brand named for Rakiura (Stewart Island) with its views of the southern lights or aurora australis.